Uncategorized

The truth about tax refunds

admin | March 8, 2019

This document is intended for institutional investors and is not subject to all of the independence and disclosure standards applicable to debt research reports prepared for retail investors.

The current tax season has been anything but normal, with the Treasury Department swept up in the federal government shutdown and the IRS officially closed for much of January. Unlike in past shutdowns, the Trump Administration determined that IRS employees handling tax returns could be deemed essential and compelled to work through the shutdown. Despite that, filing season got off to a slow start. Since the 2019 tax season is first to reflect the new tax law, early results on refunds have been closely watched by political observers to gain ammunition for arguments for or against the tax reform. Overreaction to the very early partial returns data has already proven to be misguided, as the latest data signal that anomalies early in the season were shutdown-related. The tax refund data as they stand today do not offer any major clues that can be interpreted either positively or negatively for the near-term outlook for the consumer.

Filing season basics

To start, it may be useful to review some basic facts about the annual federal income tax cycle (though any domestic reader should be quite familiar with this process!). Tax returns reference the calendar year, and returns are due on April 15. Taxpayers can file for a six-month delay, but still has to write a check to cover expected tax liabilities by April 15. The various forms needed to complete returns – W-2s, non-wage income statements, charitable donation receipts, etc. – are sent out, mostly in January. At some point early in the year, the IRS declares that it is ready to accept returns.

There are two basic rules to consider related to the timing and composition of tax return filing. First, households who are expecting a refund are likely to file as early as they can. Conversely, most households who owe the federal government money will wait until close to April 15 to file. Second, the more complex the tax return, all else equal, the later a taxpayer will file. Those with ownership stakes in a business, for example, have to wait for a K-1 report, which usually is not available until closer to the April 15 deadline. Typically most of the households who file at the beginning of the tax season are getting a refund and have relatively simple returns.

Arranging withholding levels

Each household will incur a certain tax liability for the year. That liability will be paid by some combination of withholding over the course of the year and then an April 15 payment or a refund, if the household over-withholds. Withholding strategies tend to vary by income level. Most lower- and middle-class households tend to arrange their withholding levels so that they receive a sizable refund, which is viewed as a form of forced savings. For many lower-income households, this is by necessity, since they have “negative” tax liabilities: they owe little or nothing in income taxes and are eligible for refundable tax credits, such as the earned income tax credit and child tax credit. For households with negative tax liabilities, the windfall cannot be realized until their tax return is processed. For many middle-class households, arranging withholding to receive a significant refund is a matter of choice and is done to engineer a substantial windfall that can be used to make big-ticket purchases, pay down debt, or other options that are not available to them based on relatively tight weekly or monthly budgets.

However, the “big refund” strategy comes at a cost. Getting a large refund means that a household has granted the federal government an interest-free loan over the course of the year. Most upper-income households, who are more sophisticated in their tax planning and do not necessarily need to artificially create a forced saving opportunity since they probably have other savings that can be accessed if needed, may aim to roughly break even. Financially, a strategy of under-withholding and making a big payment on April 15 would be optimal, as the federal government is essentially granting the household an interest-free loan. The IRS understandably frowns on this strategy and tends to respond to significant under-withholding by either auditing the household, asking for quarterly advance payments the next year, or both.

Incorporating these facts explains much of the inaccurate press coverage which characterized the early weeks of the 2019 tax filing season.

No litmus test on the incidence of tax reform

Political commentators, especially those who were opponents of the 2017 tax reform, were quick to jump on reports that the tax refund season began slowly to argue that the individual tax changes represented a tax hike for households with modest income. This argument was misguided from the start. First, the size of one’s tax refund, by itself, tells us nothing about the household’s total tax liabilities. When there is a major tax code change, the IRS adjusts the withholding tables accordingly based on their estimates of how tax liabilities will shift, but there is ample scope for miscalculation. The new 2018 withholding tables may have turned out to be in the aggregate more or less aggressive than the old 2017 withholding tables. Thus, in any year, but especially in a year that includes a major set of tax changes, there is no way to know for sure whether tax liabilities went up or down for any given household until after returns are processed and total taxes owed can be calculated (the combination of withholding and the April 15 payment/refund). Second, as discussed above, the earliest returns to be processed do not constitute a representative sample of the household universe. Rarely should one extrapolate from a small sample (5% or less of the population) to the whole, but it is especially dangerous to do so when it is clear that the small sample does not come close to accurately reflecting the composition of remaining households.

Shutdown impact on the filing season

As noted above, the initial assumption when the federal government shut down in December was that the IRS would be closed until a new appropriations package for the Treasury Department was enacted. However, the Trump Administration took a different view of the definition of “essential” workers, and declared that IRS employees assigned to handle incoming returns would need to come in. This was done in part to soften the impact of the shutdown on the economy as it extended past mid-January.

What did not become evident until after the fact was that while the IRS was open for business, it was not operating at full capacity. In particular, in response to rampant fraud in the earned income and child tax credit programs, the IRS had in previous years added an additional level of scrutiny to returns that claimed these credits, especially when doing so resulted in a negative tax liability. For the typical tax return, the IRS runs it through a cursory filter, and, if no red flags pop up, the return is quickly processed and a payment is made. Electronic refund payments are typically sent within two weeks or so after a return is received by the IRS (back when filings were done on paper and the IRS mailed physical checks back to refund recipients, the turnaround time was closer to six weeks). To combat fraud in the tax credit programs, IRS employees examine returns claiming these credits more closely.

Although the IRS was accepting returns in mid-to-late January, while the shutdown was still ongoing, it was not conducting these supplemental tax credit reviews. As a result, returns that were filed early in the tax filing season claiming these credits were piled to the side until the shutdown ended. Once the federal government re-opened, it took a few weeks for IRS employees to work through that pile and get back on track.

Tax return data

With these facts to rely on, the weekly tax filing statistics published by the IRS can be examined.

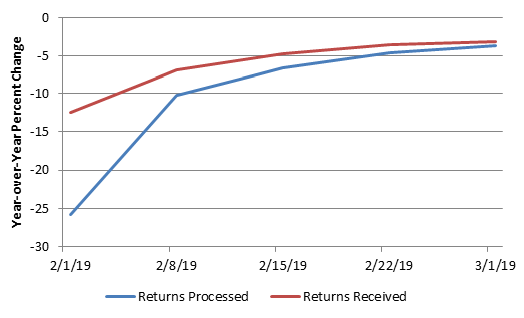

First, the number of tax returns processed has lagged behind a year ago. As Exhibit 1 shows, the IRS got off to a late start, as one would expect given the federal government shutdown. By the beginning of February, tax returns received were running about 12% below year-ago, but returns processed were down at more than twice that pace. As IRS employees began to clear the initial backlog that had developed, the gap between those two figures closed. By early March, the shortfall relative to a year ago is almost entirely due to a drop in the number of returns received. This makes sense since filing is more complicated in the first year after a major change in the tax code, so households may need longer to complete even relatively simple returns. It may also be the case that the shutdown delayed the written guidance or limited access to taxpayers’ hotlines that filers may have needed to complete their returns. As a point of reference, at the same time in the 2018 filing season, which included neither a government shutdown nor massive tax code changes, both returns received and returns processed were running almost exactly flat to the year-ago figures.

Exhibit 1: Tax returns processed – 2019 vs 2018

Source: IRS

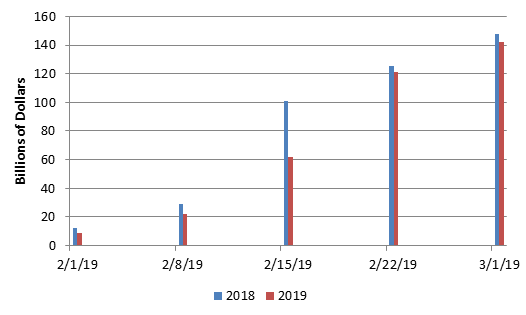

The total amount of tax refunds issued and the average tax refund are shown in Exhibits 2 and 3, respectively. Not surprisingly, aggregate refunds issued were running well below year-ago levels in early February, but commentators and even many economists, who probably should have known better, got very agitated when the February 15 data were released. As Exhibit 2 shows, at that point, refunds were running almost 40% below the year-ago level. This was the window of time when those tax-credit-heavy returns were sitting in a pile in IRS offices. A week later, as the gap between returns received and returns processed closed, tax refunds picked up, shrinking the year-over-year shortfall from nearly 39% to 3.6% in a single week. Indeed, the total amount of refunds issued in the two most recent weeks are running about 3½% below year ago, almost exactly the same shortfall as the number of returns received and processed.

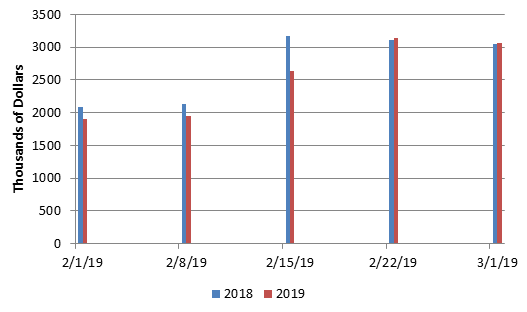

Exhibit 3 tells a similar story. Observers were fretting after the February 15 data were released, showing that the average tax refund was down almost 17% from year-ago levels. Many political commentators were arguing that this proved the 2017 tax reform was a tax hike on the middle class (a contention that, as discussed above, did not even follow), while economists were suddenly worried that the consumer would not have the wherewithal to spend (to make things worse, these data came out just a few days after the massively disappointing December retail sales release). As it turns out, those who reacted so vehemently to the 2/15 data looked silly just a week later. The average tax refund through the week of February 22 and again through the week of March 1 has been essentially level with year-ago, running a mere 1% higher. In effect, the biggest tranche of tax-credit-heavy returns were processed a week later than usual due to shutdown-related delays, and once that backlog was expedited, the numbers have been about as straightforward as possible.

Exhibit 2: Dollar amount of tax refunds issued – 2019 vs 2018

Source: IRS

Exhibit 3: Average tax refund – 2019 vs 2018

Source: IRS

Conclusion

If this piece were an Aesop’s fable, the moral would be something like: look before you leap. Too many analysts were overly eager to latch on to partial data because it may have conformed to their prior views/expectations. As the Fed has been preaching lately, patience is a virtue.

Given the major changes in the tax code that went into place in 2018, a full accounting of the tax filing season will have to wait until well after April 15. If there is a group that is paying substantially higher taxes versus a year ago, it will likely be higher-income households, in particular those in high-tax states that are losing much of their state and local tax (SALT) deductions. The tax refund data as they stand today do not offer any major clues that could be interpreted either positively or negatively for the near-term outlook for the consumer.