The Big Idea

A red hot outlook for the labor market

Stephen Stanley | February 11, 2022

This document is intended for institutional investors and is not subject to all of the independence and disclosure standards applicable to debt research reports prepared for retail investors.

With job openings at a record, the unemployment rate nearly back to early 2020 levels and wages surging, total payrolls still lag pre-pandemic tallies. Looking at the latest payrolls compared to February 2020 highlights sectors of the economy doing well and ones that have not fully recovered. Running through the jobs numbers underscores that even with an anticipated influx of workers back into the labor force this year, the labor market is likely to remain red hot.

Payroll progress

Stubbornly persistent supply constraints for labor have prevented a full recovery in employment. Millions of potential workers have remained on the sidelines for a number of reasons related to the pandemic including health concerns, a lack of available child care, the need to stay home with sick family members, and vaccine mandates. Firms have been complaining about an inability to find qualified workers for at least a year. And JOLTS job openings are running several million higher than before the pandemic, when the labor market was already quite tight.

The level of payroll employment has failed to even make it back to the February 2020 reading much less rise in line with population growth. Fed officials had talked in 2020 and much of 2021 about needing to see “substantial progress” in job gains before tapering asset purchases and suggested that they would like to see payrolls retrace the entire spring 2020 drop in jobs before considering rate increases. That framework ultimately went by the wayside as it became clear that the labor market was tight due in part supply constraints and inflation surged in a fashion that policymakers had never imagined. As a result, the focus shifted away from payroll gains late last year.

Even through January 2022, payrolls remained well below the pre-pandemic level, with overall jobs still down almost 3 million, while private sector payrolls were down by more than 2 million.

Industry breakdown

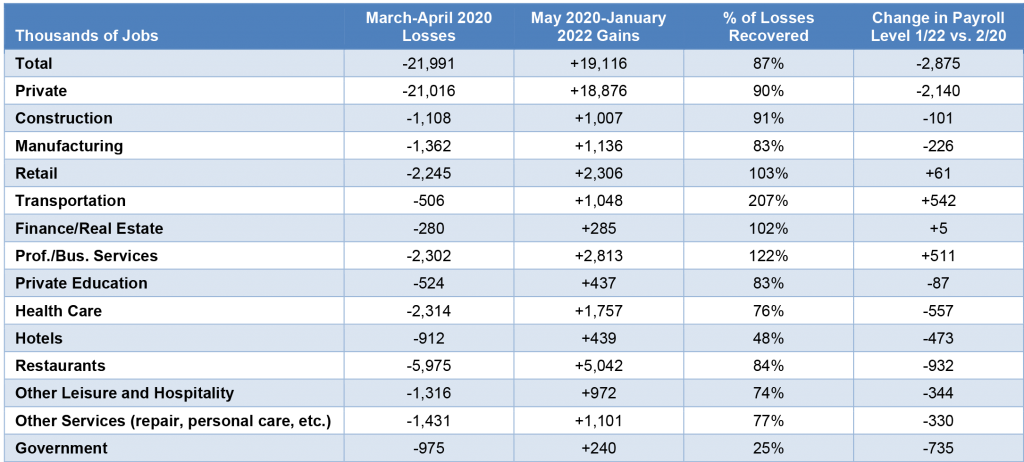

The fortunes of different sectors of the economy have varied sharply. The performance of payrolls by sector offers a window into the relative success of different industries in navigating Covid (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: Payroll performance by sector

Source: BLS.

The shortfall in overall payrolls in January 2022 compared to February 2020 remains nearly 3 million, with about one quarter of that in the government sector. However, progress has been uneven across economic sectors. With the exception of manufacturing, which remains more than 200,000 shy of the pre-pandemic level, the goods sectors of the economy have generally come close to recovering the lost ground. In fact, the transportation sector stands out as a clear winner, as truckers, delivery people, and warehouse staff have been added, more than offsetting a sizable shortfall for transit workers—public transit as well as school bus drivers.

Within services, some sectors have been able to thrive in remote or hybrid work arrangements, while others have not. Finance and professional and business services have both established new high-water marks.

In contrast, the jobs shortfall is concentrated in a few pockets of the economy. It is undoubtedly not a surprise that the largest declines during the pandemic have come in the leisure and hospitality category. Restaurants have actually recovered a higher percentage of losses than other leisure components, but the absolute size of the industry in terms of jobs still left the shortfall at almost one million. Other pieces of leisure, most notably hotels and amusement parks, are much further behind in percentage terms. We could throw in the “other services” category, including hair and nail salons and other personal services businesses, which also remains far below pre-pandemic payroll levels for the same reasons.

The second conspicuous pocket of weakness might be surprising: health care. The trouble here is that every time the virus heats up, routine health care visits get disrupted. The bulk of employment in the sector is in doctors’ and dentists’ offices. Until people feel more comfortable using health care as much as they did before the pandemic, this sector will, perhaps counterintuitively, lag, even as hospitals are desperately trying to staff up.

The third and final pocket of weakness is education. Schools have been slow to get back to normal operations, with students fully in classrooms. As a result, the level of employment for support staff such as cafeteria workers, bus drivers, cleaning staff and so on, continues to substantially lag the pre-pandemic levels.

Outside of these three industries, payroll employment is actually up slightly. These three areas reflect the pieces of the economy that have been unable to fully reopen due to the pandemic. If Covid ebbs sharply in the wake of the Omicron surge, we may see rapid progress over the next few months, assuming firms are able to find people. Many workers laid off from these sectors have likely moved on to jobs in different fields. Getting back to February 2020 levels in these three sectors would be worth roughly 3 million jobs.

Adding the supply constraint to the equation

Simply retracing to February 2020 levels would not represent a full employment recovery. Flat payrolls over a two-year period would certainly not qualify as a healthy labor market.

Roughly speaking, the BLS estimate of the working-age population has risen by 3.6 million since February 2020. If 60% of those new people were working–the employment-to-population ratio was 61.2% in February 2020 and is currently at 59.7—that would mean that we should have added another 2.1 million jobs over the past 23 months.

The shortfall relative to February 2020 in terms of employment levels adjusted for population is in the neighborhood of 5 million. A full reopening of the economy would likely create somewhere in the neighborhood of 3 million jobs, mostly in leisure and personal services, health care, and education.

With labor demand red hot, the JOLTS tally of job openings is roughly 4 million higher as of December than in February 2020. The reality is that, even with some parts of the economy still hamstrung by Covid, the economy has in fact created almost all of the jobs needed to get back to pre-pandemic employment-to-population ratio readings.

However, firms have been unable to fill those openings due to reticence on the part of individuals to return to work. The shortfall in labor supply likely reflects several factors. First, and probably most importantly, the massive lockdown-driven layoffs in the spring of 2020 led to a wave of early retirements. Those workers who might have been within a few years retirement anyway would in many cases have simply stepped away. The generous federal payments distributed in 2020 and 2021 and the massive appreciation of household assets—mainly stocks and homes—would have made that decision much easier. Several independent research papers by various Fed economists estimate that as many as 2 million to 3 million workers above and beyond the expected trends retired in 2020, and most are unlikely to return to the labor force.

There are others sitting on the sidelines who will be more inclined to return but are waiting until health concerns die down or perhaps are struggling to procure quality childcare. Or perhaps they are taking a hiatus, living off the extraordinary fiscal largesse of 2020 and 2021.

Let’s say that 2 million people come off the sidelines and rejoin the labor force in 2022 above and beyond the normal rise associated with population growth. Based on the JOLTS job openings tally, we can presume that they would be snapped up relatively quickly still leaving 9 million unfilled openings. The payroll gap would be mostly closed, and the labor force participation rate would be around 63%, just below the February 2020 reading of 63.3%.

Even in that scenario, however, torrid labor demand would mean that the labor market would remain historically tight. Add together the 2 million people who might come off of the sidelines this year to the 800,000 increase in unemployed in January compared to February 2020 and there still are not enough people to fill all of the 4 million extra JOLTS job openings. And that is before the economy creates another 2 million jobs in sectors that have yet to fully reopen. In sum, no matter how you slice it, labor market tightness is likely to remain with us in 2022.